It’s been 10 years since Alyssa Dreiver’s twin sister died, but people still mistake her for Anissa.

They were identical, with blonde hair, brown eyes and matching smiles. When they spoke the same word at the same time, their throats would vibrate, Dreiver said.

But then a driver hit Anissa’s car head-on, killing her instantly when she was 25 years old.

Losing Their ‘Other Half’

“On February 1st 2004, my world was shattered,” Dreiver, now 35, told ABC News. “When I looked at her in the casket, I felt as if I was looking at myself.”

The two were inseparable growing up in Oklahoma, Dreiver said. They wore matching outfits, but in different colors. When Dreiver cut her hair during her senior year of high school, Anissa cried because they no longer looked exactly alike. Even after they moved to separate cities and got married, they would still drive six hours to see one another every few months and sleep in the same bed.

Though Dreiver had experienced other close family members’ deaths, Anissa’s death was different, she said.

“Anissa is half of me. She is half of my soul. She’s a part of me. She’s my best friend. She’s like my shadow,” Dreiver said. “And I no longer have that.”

Dreiver said she has had a hard time coping. Every time she looks in the mirror, she remembers what she lost, she said.

Finding Twinless Twins

Last week, Dreiver found a Facebook support group for “twinless” twins – people who have lost their twin.

“I already feel a wonderful connection with them that I haven’t felt with any counselor or friend or anything like that,” she said. “No counselor I have ever been to can help me because they don’t understand.”

The national Twinless Twins Support Group has been around for decades, but the Facebook group has helped connect even more people over the last few years, especially those between 25 and 35 years old, said the group’s administrator, Dawn Barnett. Although there were 250 Twinless Twin Facebook group members in 2012, there are now nearly 1,500.

“We believe that by helping other twinless twins who are grieving, it helps you,” Barnett said, echoing Alyssa’s point about how other people don’t quite understand. “Twin loss is so deep because you were bonded from the womb on.”

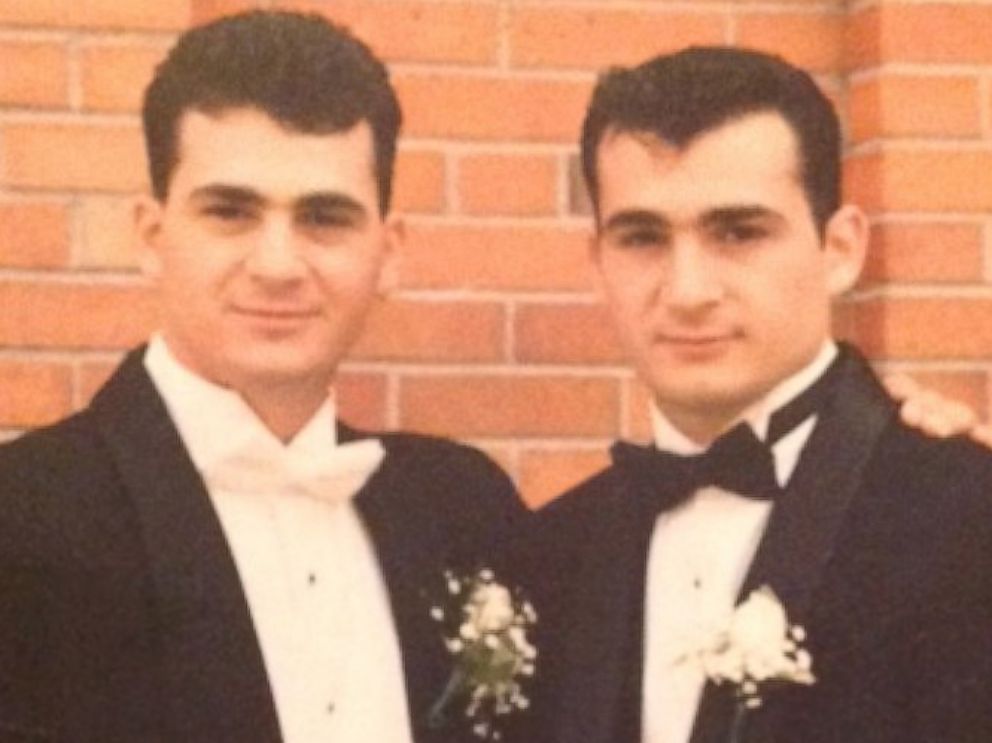

Domenick Abbate, 40, who said he always felt like the big brother figure to his twin Frank, said the two of them were so close that they swore they could share dreams as children.

Frank, a canine handler for the New Brunswick Fire Department following the September 11 attacks, died of lymphoma in 2010, Abbate said. He tried to keep moving forward, but eventually he started drinking, missing work and experiencing marital problems.

“The minute I got home, I wanted to crawl into a ball,” he said. “You still feel that missing connection. It was basically eating me up inside."

His wife was the one who found the twinless twins group and suggested he go to their annual conference in mid-July. He felt an almost immediate connection, he said. He loved how the group members would know when he needed a hug even before he did.

“We almost all had the same story in the end -- how we were feeling” he said. “No one else understood. My sister, my mother, they all say ‘I understand how you feel,’ but they didn’t.”

No Longer Living as ‘We’

Carolyn Landis, a psychologist at UH Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio, said how someone handles the death of a twin can vary depending on a variety of factors, including how close the twins were and even how much they looked alike.

“Especially with identical twins, you would remind yourself of your twin,” Landis said. “It’s a similar phenomenon to a parent that loses a spouse and sees aspects of their spouse in their child.”

Landis said the surviving twin should focus on how he or she is unique as part of the healing process. Writing down memories in a journal can help, too.

But regardless of whether twins are identical, Landis notes that they went through every milestone -- from starting kindergarten to leaving for college to turning 30 -- together. Experiencing new milestones alone may be especially hard for the surviving twin, she said.

“Now you’re a single person, and you’ve been living as a ‘we,’” Barnett said. “You live a different normal.”

Landis said that technology from Skype to unlimited long distance calling can keep twins connected in a way that growing up might have pushed them apart in decades past. As a result, the death is painful even if twins didn’t live in the same city.

Landis said some surviving twins may fall into depression and should not be afraid to seek help from a therapist. Some survivors seek religion, too.

Early Twin Loss

But not all surviving twins remember the twin they lost. Dawn Barnett, who runs the Facebook group, said her identical twin died when the two were 10 months old in 1948. “All my life, I felt I wasn’t a twin because I didn’t get to live with her,” Barnett said. “My parents were in such grief. My parents never talked about her.”

But she came to embrace being a twin after seeing the Twinless Twins Support Group on a talk show in the mid-1980s and deciding to get involved.

Barnett felt especially close to her twin after having a heart attack in 2005. Her twin’s cause of death had been a heart problem in infancy nearly six decades earlier. Barnett spent several days in a coma and said her twin came to her and told her it wasn’t time to die yet.

At the annual Twinless Twins conference this year, about 120 attendees – 10 percent of the total group – lost twins in utero or as babies, Barnett said, noting that the organization doesn’t keep statistics.

Kevin Mullen, 33, of Vermont, is among them. Mullen’s twin died when his umbilical cord wrapped around his neck and a blood clot formed, he said. Mullen himself was born with cerebral palsy. The only photo Mullen has of the two of them is an ultrasound photo.

“I’ve always been around twins. I have twin cousins, several sets of twin cousins,” he said. “Even though I do miss my twin, I honor him in different ways.”

Mullen happened upon Twinless Twins in the 1990s and said he honors his twin by participating in memorial walks and fundraisers for the group.

He said milestones, like turning 16 and going to Europe, always made him think of his twin because it would have been something they could share together.

" />

" />

Kendra Felder, 24, said she feels the same way. She found out about her twin sister when she was about 8 years old. Her twin, Courtney, died 11 days after they were born premature. On their birthday, she said she likes to find Courtney’s baby blanket and put it in a shadow box. She always thinks of her twin when a friend or family member dies and when she finds herself in a period of transition.

Landis said she’s had patients who don’t remember their twins but still think about them and talk to them.

“The fact that you were together in the womb, there’s something about that connection,” Landis said.

It’s important for parents to be transparent about the deceased twin by talking about it openly and making sure the surviving child doesn’t feel guilty, Landis added. The missing twin should never be a secret, and may even become a source of comfort.

Remembering Anissa

Driever talks about her twin sister, Anissa, every day even though she’s been dead for 10 years, she said. When she switched jobs, her coworkers said they felt like they were losing two people instead of just one because Driever talked about Anissa so much that she became alive for them.

“I love whenever somebody mistakes me for Anissa,” she said. “It warms my heart because I don’t want my sister to be forgotten. I talk about her or I think about her every day.”